A visit to The Last Days of Pompeii: The Immersive Exhibition

- Dec 16, 2025

- 7 min read

I’m always up for a bit of technology and Classics. In this case, a friend pointed out this immersive exhibition at London’s Excel exhibition hall in Docklands. There was a YouTube video as well. It looked – kind of okay. Still, nothing ventured, nothing gained. We went along. It was Sunday, about 1pm.

It took some time to find the place as it was located in an exhibition space under the main Excel centre rather than in it: access was literally on the dockside. Inside, it looked like they were expecting hundreds of visitors, but the place was eerily quiet. My friend suggested that we had been scammed – perhaps It was going to be like one of those infamous Christmas Experiences one reads about, where there’s only a couple of potted fir trees and a plastic reindeer festooned with fairy lights for your £30 admission ticket.

Our expectations were quite low at this stage. The bag check man waved us through and a cheery man took our tickets. There was no queue. As far as we could tell, we might be the only people there. Another friendly man took our photos – looking up as if we were being fired out of the volcano’s crater (we later learnt) and standing against a generic Pompeii view. We chose not to buy.

Inside, we were greeted by a series of rather unimpressive rooms – too large for the small number of objects in them. The walls were enlivened by large displays, illustrated a bit like walking through the pages of a giant book. Indeed, I recognised a few of the pictures from published works – I do hope they got their permissions done! The text was fairly standard: when was Pompeii built, daily life, food, religion, sports and entertainment. It was pleasant enough but not earth shattering. The display objects came from Spain rather than Pompeii, were few and far between, and padded out with reproductions such as the Dancing Faun or a soldier’s sword. I’m not selling it to you, am I?

Nevertheless, we ploughed on. It did become a bit better from now on. First, there was a room where we sat in swivel chairs with Virtual Reality (VR) headsets on. A track played in which we followed a chariot team through the countryside into the city and into an amphitheatre. Dropped off in the arena, we watched a contest between two gladiators at close quarters. There was no blood or hacking off of limbs, but it was pretty violent. With the headsets, you could look all around as the crowds did the traditional cinematic arm waves and air pumps. One gladiator was dispatched in a rather unusual way – I won’t spoil the fun, except to say that ‘this never happened in real life’. Enter a tiger, and more fighting. To be fair, it’s pretty good and a long way in advance of anything I have seen before by this technology. Next, the amphitheatre is flooded and we are now like fishes underneath while great warships (which have miraculously entered the fray) ram each other, crash and burn. A certain amount of artistic licence has been applied.

Another room demonstrates the Fiorelli process, with some plaster casts from Pompeii dotted about (barely labelled, they seem to be ignored by the visitors). There’s reference to the Pompeii dog, but no Pompeii dog. A group of adults and a child sit forlornly in the middle. I personally found this room to be the most desolate of all – not because of its subject matter, but because nothing had been made of its subject matter.

Next along is another room – much larger than the others. In it, a continuous immersive cinematic film plays – which covers the walls and the floor while we sit quietly on padded cubes. There’s a rather unconvincing narrative, which blends, as the exhibiters say, ancient and modern storylines. Thus, we get some fantasy involving (I think) Plautus and the Dancing Faun, a giant rotating eye, some of Edward Bulwer Lytton’s ‘Last Days of Pompeii’, and selections from Pliny the Younger all flung together. The organisers in the video suggest ‘Why not?’ Others might ask the question ‘Why would you?’ when there is plenty of reality to work with. Nevertheless, it’s a heady mix and the visuals are very good, in a technical sort of way, if a little hyperbolic. After a frankly weird introduction, we rush to the city through the gate (not any I recognize) into the town centre. We enter a Pompeian atrium, and goldfish swim beneath our feet as the floor turns into a giant impluvium. On the walls, characters turn to life amid the statues: a slave girl anticipating being set free; Pliny the Younger and his mother arguing about his homework. The rumbles start and we all know what happens next. We enter the fiery centre of the volcano (quite well done, if over-long) and then Pompeii is destroyed before our eyes by a mixture of pyroclastic flows and firebombs (the latter not recorded, I think). Some of the inhabitants of Pompeii aren’t lucky enough to escape. Ignoring what we know about Fiorelli’s process from the other room, they stand, turned to ash in poses reminiscent of that awful film Pompeii from a few years back. Figures from the Villa of the Mysteries come to life and then blow away in a hail of dust. There are lizards on the floor.

After the excitement, Pompeii lies buried until its discovery. Here, a special mention is made of the Spanish King who ordered excavation. This is a Spanish exhibition, so I suppose he has to take the credit. It was curious, that, what with the Spanish artefacts, it felt like Pompeii was barely Italian or in Italy.

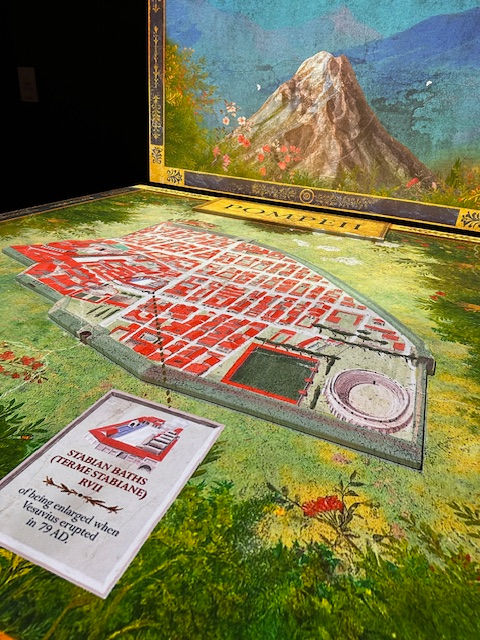

Another room, with some large well-illuminated displays – a plan of Pompeii, where you can find the baths and the forum etc, and some touch-sensitive exhibits which brought up text or film to ‘show you how’. Nothing radical here, but enjoyable, if you like that sort of thing. Most of the children in the exhibition touched once and walked on. It must be galling for the designers to watch their hard-earned technology so casually ignored. There was a graffiti wall, to leave your mark like the Romans did. This seemed more popular, suggesting old habits die hard, even among the young. I noticed that while the text on the giant displays was accurate, the designers had clearly used GenAI to make some of the images, with the result that the spelling of Latin was incorrect and some texts impossible to decipher. There was a feeling of ‘AI-slop’ around the images too. Is this a telling moment for our times?

Last of all – we were beginning to feel hungry by now – was, in fact, the pièce de résistance: a fully immersive VR experience. Now I am going to say it: this made the whole thing worthwhile. With the full immersive headsets placed on by the guide, we walked into – a full-sized Pompeian domus-type house. From the outside, all we could see were people walking about in a large empty space. Wearing VR headsets we were as if inside a three-dimensional building. We could walk around, up to the ‘walls’, go through ‘doors’, stand on the threshold of the ‘atrium’, peer over the ‘balcony’ at ‘the garden’, observe the ‘oven’ in the ‘kitchen’ and the ‘lararium’. A clever system meant that we could ‘see’ others in the room, so we did not bump into each other. Nothing was real, of course. It took a time to realise that you couldn’t lean on the ‘balcony’ or pick up the ‘frying pan’. The rooms were – how shall I say? – more representative of the Pompeian domus rather than accurate copies. This was a shame, because the lararium was magnificently recognisable from the House of the Vetti, all lit up with offerings and candles sputtering into the darkness, but its proportions and setting were wrong. But the VR experience really did show what could be done, and in ten years this might be one of the standard ways our students learn about the ancient (and modern) world.

Somehow, the VR technology picked out our own hands, which gave us a sense of stability in what would be an otherwise disorientating world. Each room started as a ruin, became fully created as it was 2000 years ago, and then returned to ruins. This sense of each room being an episode meant that we were kept moving. A running commentary – as of a Pompeian woman leading us through the house – kept things moving along, but not at a hectic pace. At the end, headsets off, we marvelled at how the people we could see walking apparently randomly around the room were – just like we had been – thinking they were walking around a decent-sized Roman domus. The system must ensure that the sequence and placement of room experiences do not overlap – else people will crash into each other. I have to say that the technology was amazing. For obvious reasons, it is impossible to take pictures, but the YouTube presentation gives a flavour if you want to have a look.

So, from there we stumbled. The exhibition, despite its flaws, is worth a visit, if only for the VR experiences. A Classics teacher will find lots to grumble about. School students will probably not be terribly impressed with the non-interactive exhibits - but the VR experiences of the gladiator fight and the walk-thrus of the domus might make up for it. The eruption of Vesuvius part of the immersive film might provoke more questions than provide answers - but that might be a good thing. Education should promote questions.

It’s at the London Excel Waterfront exhibition centre from 14 November – 15 March, from where it goes on an international tour. Details are here.

Comments